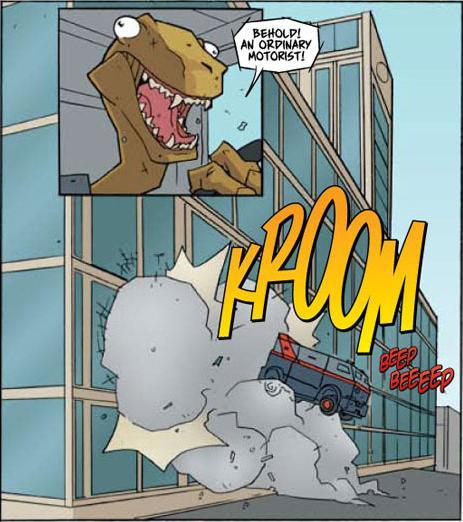

This week I’ve been corresponding with Brian Clevinger – the creator of the now finished webcomic 8-bit Theater, and the writer of superb adventure comic Atomic Robo.

Todd Marsh: For those who don't know, how did your webcomic work begin?

Brian Clevinger: 8-bit Theater began completely by accident. I had just finished writing my first novel so it was time to find something else to waste all my time. I’d just signed up for an Independent Study course focusing on comics at the University of Florida. So, hey, I’d make my own comic from scratch and talk about the intersection between practical and theoretical concerns.

I used old video game images because I cannot draw. At all. Any gorilla could out-draw me, no contest. I made the comics funny just to keep myself interested enough to not fail the course. I put the pages online because my professor was terrible at keeping track of emails.

About nine months later I dropped out of college to work in comics full time.

TM: And how did that lead to print comic work? Would you say that one was a stepping stone to the other?

BC: Well, our publisher contacted us because of some concept art I posted on my webcomic site. So, yeah, having a catalog of online work certainly didn’t hurt.

TM: Do you find that the different mediums affect your writing style? For example, the audience reading one webcomic page at a time versus reading one whole issue of print comic at a time?

BC: Sure, in print, you can generally see the next page, but it’s in the periphery. So, I’d argue that you’re always reading one page at a time. It’s just that there’s a much larger pause between the current page and the next one when you’re keeping up with a webcomic as it’s being produced.

You should seek to make each page worth reading individually whether you’re in print, online, doing a linear narrative, or just random gags. I took that thinking from the internet to print. You’ll notice in Atomic Robo we don’t really transition from one page to the next. A scene may happen on multiple pages, but each page is its own object.

There’s something meaningful or interesting on every page.

But really the main change for me was the introduction of structure. Glorious, beautiful structure. 8-bit Theater is over 1,200 pages because I had no structure. Every page was just whatever I thought would be funny or interesting that day.

With print comics, you’ve got 20/22 pages to an issue and that’s all the space you’ve got to tell your story or your chapter. So, it’s like the “every page is meaningful or interesting” but blown up in scale.

When your story is constrained by outside forces, that’s when you get clever about how to tell it.

TM: Do you find one medium easier to write for than the other?

BC: They’re pretty same-y, really. You can get super experimental with online and digital content in a way that print can’t replicate, and I’m glad we have people out there tackling that material, but it’s not the stuff I’m interested in creating. I’m boring and old and just want to make comics that are fun and accessible to anyone.

TM: The perception is that webcomic fanbases are more connected to the writers due to things like page comments and social media, would you say that's true?

BC: It’s certainly the perception, because all the tools for getting a webcomic onto screens are the same tools that get our personalities onto them too. But ultimately it comes down to how much effort the author makes to connect or to not. You can be the most directly accessible print guy or the most hermit-ed webcomic guy.

TM: Can we talk money? Is it easier to make money from print comics?

BC: It’s easier to get money out of print comics, because there’s so much momentum in the industry and its patrons that things cost money. Publishers, contracts, retailers, page rates, advances, royalties, and customers who expect to pay for the things they love are already baked in to print.

That said, the potential pay day in webcomics is much higher because you cut out the middlemen. It’s just you, the customer, and the cost of production. But it’s a much riskier game to play.

TM: Should print comics and webcomics be competing or sharing the marketplace? Do they even have the same "customers"?

BC: There is no real competition and the idea that one of these takes dollars from the other shows a terrible ignorance of the marketplace.

People want comics. This is a fact. Because of webcomics, more people habitually read comics today than at any time in our lives. The vast majority of these people didn’t come into comics reading through the print industry. The inane ins and outs of publication and retailers and Diamond Distribution are not a part of their world, and more importantly, would not be tolerated by them.

But they want comics. And, to them, reading comics on a screen is perfectly natural. Even preferred. In what way is this customer served by physical copies?

Conversely, if I want a trade paperback because I enjoy the act of owning a material copy and the physical experience of the object itself, then the digital material isn't of interest to me.

It would be idiotic to ignore either customer in a world where each can be easily catered to.

TM: What are your views on the relatively recent surge of digital copies of print comics? Would you say that digital copies are the future of the industry?

BC: Comics are pulp. They’re disposable entertainment. But there is nothing disposable about printing them on high quality glossy paper and selling them for $4.00. Digital storage and bandwidth are much, much cheaper. And getting cheaper. That’s pulp. That’s disposable.

Digital distribution is the future. That’s math talking. That doesn’t mean the death of print, and that doesn’t mean that publishers can’t thrive. It just means they have to adjust their services to match the evolving marketplace.

Oh, and they need to stop charging print prices for digital material. It’s absurd.

TM: Of course, print comics are very much in the general public's mindset what with all the films and TV shows around at the moment. Do you think we'll ever see anything similar with webcomics? Will [popular webcomic character] ever become a household name?

BC: Absolutely. Hollywood doesn’t care where ideas come from if there’s a dollar to be made.

There’s this great bit in Wodehouse where a producer, in this case of plays, decides whether or not to back plays based on what his eight year old thinks of them because your average audience is about as smart a small child.

So, if you thought Reality TV was intensely cynical, look out for the next Big Idea: whimsical and magical stories written by any 5 year old. Honey Boo Boo is the bridge.

TM: Finally, feel free to use this space to plug anything you need to plug.

Here’s all the Atomic Robo news that’s fit to print. http://www.atomic-robo.com/

Here’s where I write free fiction and blogs about writing. http://www.superexplosive.com/

Todd Marsh would like to thank Brian Clevinger for taking the time to provide us with his insights.

No comments:

Post a Comment